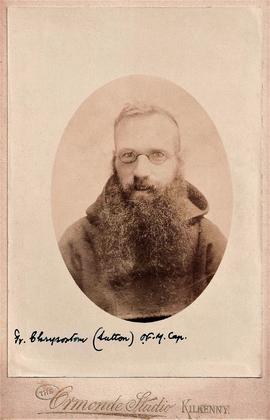

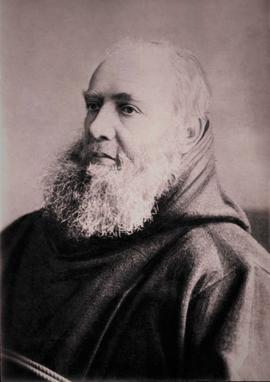

James Tommins was born in Dublin on 29 March 1812. Often, when recounting the difficult conditions in pre-emancipation Ireland, he would tell his younger fellow-friars: ‘You were born free. I was born a slave’. As a youth he was apprenticed to a haberdasher, or, more specifically, a button-manufacturer. He frequently attended religious services at the Capuchin chapel on Church Street. In his late thirties, Tommins expressed a desire to become a Capuchin friar. He went to night school to gain the necessary knowledge of the classics, and, by assiduous study, he soon reached the standard required for the novitiate. Then, in 1849, at the age of 42, he was sent to Bruges, in Belgium, for his novitiate and studies. Having taken Edward as his religious name, he was noted for his strict obedience and generous self-sacrifice, which, together with his profound humility, won him the esteem of the Capuchin community in Belgium, and secured his admission to profession. With the successful completion of his studies and having been ordained priest in 1856 by Jean-Baptiste Malou (1809-1864), Bishop of Bruges, he returned to Ireland. The following year Fr. Theobald Matthew OSFC, then Commissary-General, assigned him to Kilkenny. Except for a short period during which he was guardian (local superior) in Cork in 1861, Fr. Tommins spent his entire priestly life in Kilkenny, most of the time as guardian of a small fraternity of two or three friars. He prepared the way for the establishment of a Capuchin novitiate in Ireland; and, at a later period was appointed Commissary-General. On 23 January 1861, Fr. Edward called a meeting of the people of Kilkenny to arrange for the furnishing of the friary church. The meeting was presided over by the Mayor, Thomas Power, and it was agreed to engage Mr. McCarthy, architect, to oversee the improvements to the church, including the installation of the high altar. Once the church was completed, Fr. Tommins was also responsible for the purchase of the garden as far as Pennyfeather Lane. He also gave occasional missions and retreats notably in Castlecomer, Clough and Urlingford. With a shortage of Capuchin priests in the Irish Province, he sometimes said one Mass in Dublin on a Sunday morning; and then took the train to Kilkenny to say a second Mass there. He was also responsible for the inauguration of the Third Order of St. Francis lay confraternity in Cork in about 1866. Of the first six men he recruited as tertiaries, two joined the Capuchins: Br. Joseph O Mahony OSFC (d. 1902) and Br. Felix Harte OSFC (d. 1935). Fr. Tommins was also one of the first to take the pledge when Bishop (later Cardinal) Francis Moran, founded the Total Abstinence Sodality in Kilkenny. He died at the Capuchin Friary on Walkin Street in Kilkenny on 29 July 1889 and was afforded an elaborate public funeral. He was laid to rest in a tomb adjoining the northern aisle of St. Francis Capuchin Church in Kilkenny.

Baptismal name: James Tommins

Religious name: Fr. James Edward Tommins OSFC

Date of birth: c.29 Mar. 1812

Place of birth: Dublin

Name of father: Nicholas Tommins

Name of mother: Mary Tommins (née Casey)

Date of reception into the Capuchin Order: c.1830

Date of ordination (as priest): 1856

Date of death: 29 July 1889

Place of death: Capuchin Friary, Walkin Street, Kilkenny